The world of educational reform overflows with methods and strategies to solve perennial challenges. Classroom behavior problems? Try a new classroom “management” strategies. Struggling with student disengagement? Reach for “personalized learning.”

But for certain “reformers,” classroom interventions merely tinker at the edges, failing to target the perceived root of the problem: public education itself.

Welcome to neoliberalism.

Neoliberalism is a worldview grounded in the principles of free markets, limited governmental intervention, meritocracy, and personal responsibility. As an economic philosophy, neoliberalism is seen in policies such as free trade or the weakening of environmental and labor regulations—practices that gained ground in the 1980s in response to decades of Keynesian policies that favored more governmental intervention. Today, neoliberalism reigns today as the dominant global economic paradigm.

Neoliberal Influences on Education

When applied to public education, neoliberal logic sounds like this: “Public schools are inherently inefficient because they limit choice and reward mediocrity by accepting any kid who walks in the door. It’s time to revolutionize the stultifying, factory-model education that is crippling global competitiveness. To save public education from itself, we must throw open the doors to the private sector: “edupreneurs,” venture capitalists, and multinational corporations.”

At first glance, it sounds kind of appealing. Who doesn’t like innovation? Who hasn’t been bored stiff by the rote learning and compliance too many of us have experienced in our educational careers? But when we dig a little deeper, we see questionable impacts on key facets of schooling, including its purpose, governance and accountability, and curriculum:

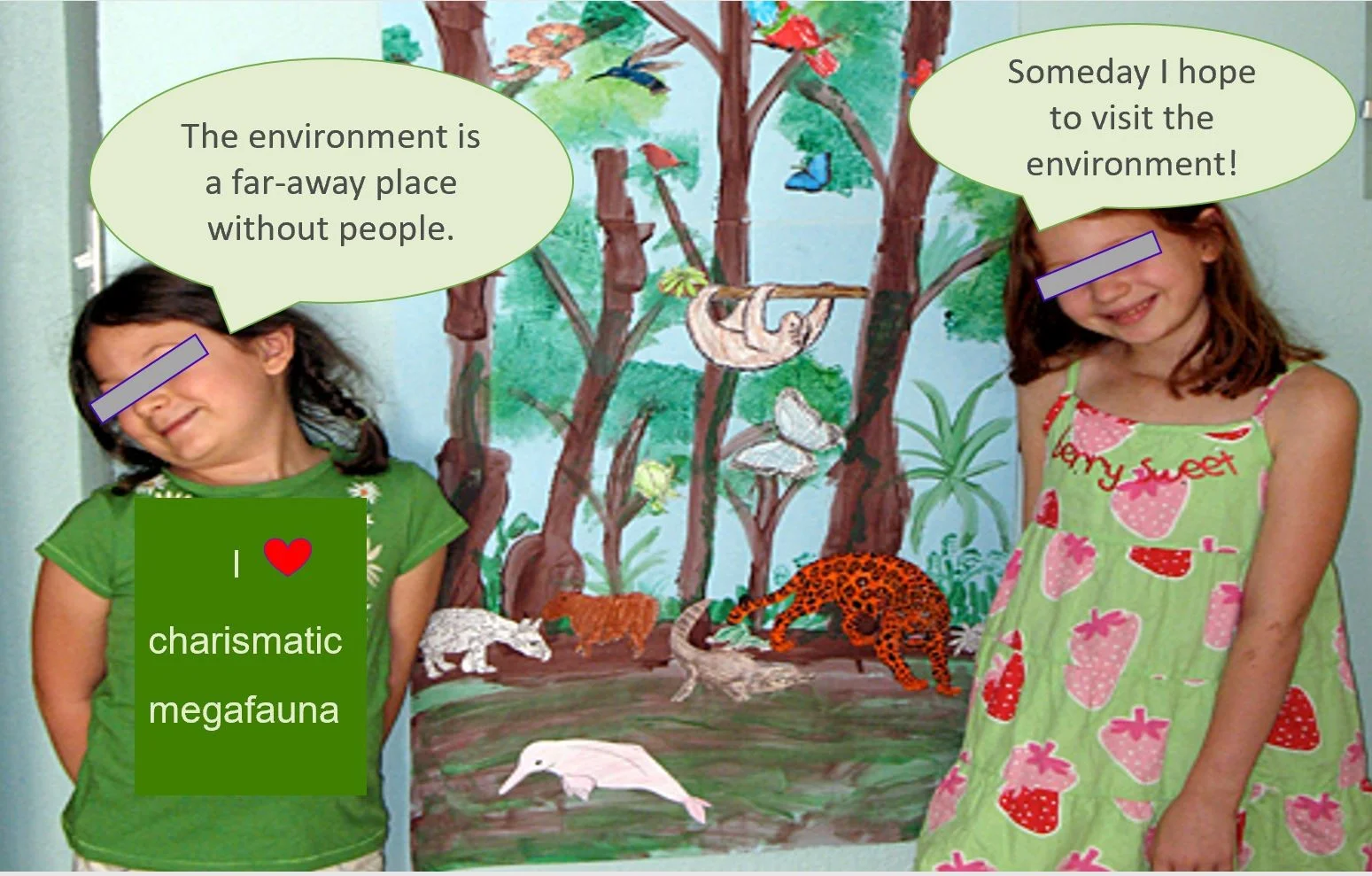

The purpose of school: In neoliberalism, the educational system’s primary purpose is to prepare students (“consumers”) to be competitive in the global economy. The larger goals of preparing students to be empathetic individuals, critical thinkers, and citizens are tangential or even contrary to neoliberalism’s focus on economic growth. For example, asking critical questions about the carrying capacity of the environment calls into question the primacy of raising the GDP.

Governance and accountability: Neoliberalism’s disdain for the public sector is seen in the form of vouchers, for-profit charter schools, and other schemes that direct public funding to private actors. The logic here is that competition will inject much-needed motivation and innovation in a system that’s being smothered by its own bloated bureaucracy. If schools were responsible to shareholders, not the public, we’d have real accountability.

Views of inequality: Neoliberalism hinges on an unquestioned belief in meritocracy. In this view, high-stakes testing serves as sound policy because it sorts winners from losers. Disparities in outcomes based on race or socioeconomic status are simply proof that “those people” don’t value education or are inherently (dare we say genetically?) inferior. In this mindset, solutions for improving achievement should focus on raising the bar, clear rewards and punishments, and fixing faulty character and morals.

Curriculum: Neoliberal shows up in curriculum in both overt and subtle ways. Examples:

Economic textbooks that present only conventional models--models that externalize environmental impacts as “externalities” or “market failures.”

Coded language about “developed” and “undeveloped” countries that champions Western industrialization, whitewashes its colonial roots, and marginalizes indigenous perspectives.

A narrow focus on tested subjects (primarily math and English) at the expense of arts, physical education, or anything else deemed dispensable or peripheral to “real” learning.

Efforts to eliminate world language courses and replace them computer coding.

Keeping the “Public” in Public Education

It goes without saying that jobs are important and that businesses, like all sectors of society, have a stake in our educational system. Moreover, bureaucracy in any sector is burdensome and frustrating. But neoliberalism isn’t just about improving management; it’s about changing the very nature of public education. Neoliberalism’s creeping influence is eroding the civic mission of schools and redirecting it to serve ever-narrower ends. The case here is thus not against improving education, but for changes that preserve public accountability and the commitment to equitably serving all students.

Here are the questions we need to be asking ourselves: To what extent will society be able to meet civic goals if schools only prepare children to meet economic ones? The answer may lie in the questions we pose of our educational system: What do communities need from citizens? This question will yield a very different response than, What does the economy need from its workers?

Interested in learning more? You may enjoy the following:

My journal article, “Reclaiming Education as a Public Good”

This document, which comparing neoliberalism with sustainability.

My book, other blog entries, or free classroom resources.