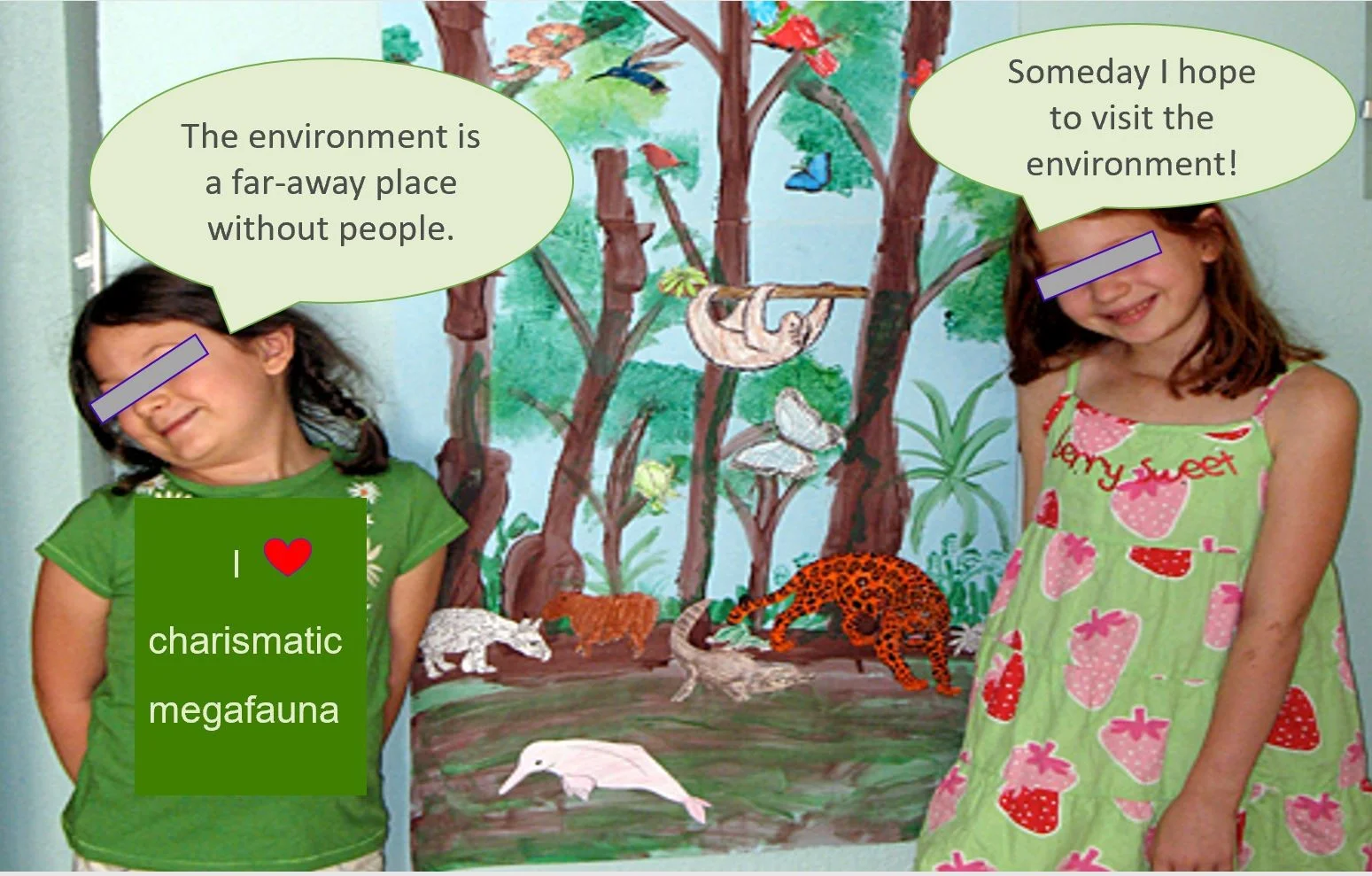

Earth Day is here again, and kids around the country may well be busy making endangered species posters or constructing a paper mache rainforest. Such projects—mainstays of what I call Environmental Ed Lite—can be fun. But focusing on exotic animals and ‘wild’ places sends the message that the environment is a place both far away and without people. That keeps kids from understanding a vital and basic scientific fact: humans are part of the environment.

“Green” learning that prioritizes stereotypical topics such as rainforests and endangered species—however important—doesn’t advance the more complex critical thinking and civic engagement goals of sustainability literacy. Can the student who draws a rainforest toucan identify a bird that’s native to the local ecosystem? Can the student who made an Amazonian kapok tree name an indigenous tribe that inhabits the forest? I wonder. Perhaps most significant, presenting the environment as external to students can inadvertently reinforce the idea that the natural world is at our disposal—an anthropocentric mindset that is not innate but learned.

Place-based Education

How can we change the story? One approach is place-based education (PBE). PBE situates environmental literacy in the actual places students inhabit, making the community the starting point for investigating environmental, cultural, political, and social phenomena. PBE views the world as it truly is—a system—by using local environment conditions, cultural perspectives, and historical events to teach concepts in practically any discipline. PBE can happen inside, outside, or both.

Place-based education is not simply about (for example) interviewing local residents as a point of interest. Rather, PBE cultivates students’ identities as members of ecological and civic communities with a shared stake in common issues. PBE fosters students’ capacity to solve real problems, and used as the basis for project-based learning, PBE provides immediate relevance. Because students engage with issues right outside their doors, they naturally raise questions complex enough to support meaningful projects.

For example, in a rural community in Oregon, students in an interdisciplinary STEM course focused on the redevelopment of a “brownfield” (a contaminated site) located on school property. Working with state and local agencies, students investigated the history of the site, soil and water quality, and associated health risks. As a final project, students created redevelopment proposals and presented them at a state brownfields conference. In addition to impressive academic gains, the course also provided student exposure to career pathways in STEM, law, public policy, and more.

Global learning starts at home

Place-based education doesn’t discard a global perspective, but rather gets there by starting at home. For example, to bridge local ecosystems and the Brazilian rainforest, students might compare the two ecosystems and (as age-appropriate) learn about indigenous tribes, the impacts of industrialization, revitalization movements, and ways our own consumption habits affect it all. Including social justice themes ensures that place-based education doesn’t neglect—or even reinforces—colonial mindsets by remaining silent on the cultural or ecological ramifications of “development.”

Is it time to clear-cut the paper mache rainforest? Not necessarily. But let’s raise the bar. Environmental literacy is an essential 21st century skill that will determine life in the 22nd century. Our kids deserve the best we can give them.

You can learn more about place-based education in my book, Reframing the Curriculum.