The arrival of spring and Earth Day is a great excuse to get outside (assuming you can, and with social distancing, of course). Nonstop screen time from our digital, quarantined lives makes us even hungrier for the physical and mental renewal nature can bring. And although we have fewer options for outdoor activities, we may still find smaller pleasures: buds on a tree, flowers peeking through the ground, the music of birds, or simply the opportunity to put the snow shovel away.

Read MoreSocial Justice: More Than Kindess

This piece is a guest post hosted by the Equity and Inclusion team of the Michigan Chapter of the Society for Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators. A huge thanks for the opportunity to share my thoughts and for the use of the team image.

Read MoreA Look Inside My Social Justice Education Course

As the anti-racism movement strengthens, so must efforts to prepare educators to respond through school structures, policies, and classroom practices. This is the rationale behind “Teaching Towards Social Justice in Secondary Education,” a graduate course I teach at the University of Michigan School of Education.

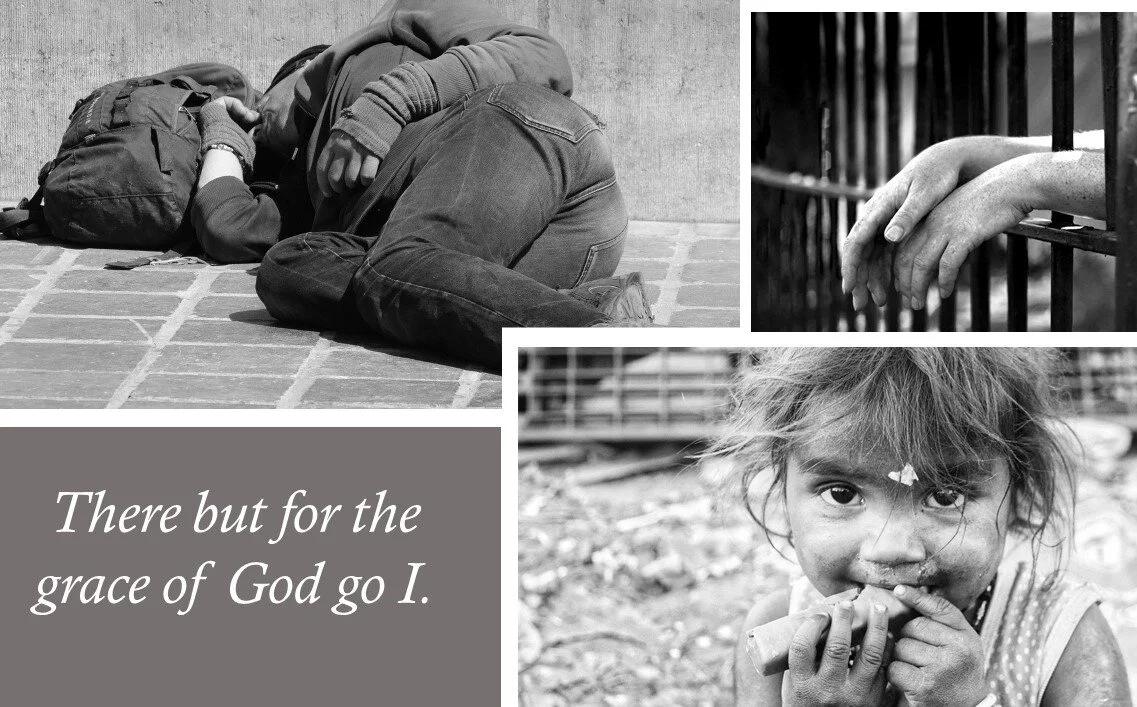

Read MoreDefining Social Justice

The phrase “social justice” is increasingly prominent in the public discourse, especially in discussions about race, the justice system, and education (my field). A loaded phrase, the mention of social justice can provoke anger, resistance, and apathy. Those supporting social justice may see it as a call to action.

So what does it actually mean? An informal Google search yields a torrent of scornful blogs and videos mocking so-called snowflakes,We safe spaces, political correctness, and all else disparaging of so-called “social justice warriors.” I’m venturing a guess that the hysteria is intended to deflect attention away from oppression--the opposite of social justice. So let’s start there.

Briefly, prejudice and bias are negative beliefs and attitudes, and stereotypes are simplistic generalizations. Prejudicial beliefs and stereotypes can lead to discrimination, the act of denying access to goods, resources, respect, and services to people based on their membership (real or perceived) in a particular social group (Stephan, 1999). Oppression goes beyond individual acts of discrimination and weaves discrimination into the structures of everyday life, including schools, the judicial system, housing, and more. That’s why we’ll also use terms such as institutional discrimination to describe the structural, systemic barriers it presents.

Oppression is characterized by hierarchies of races, genders, etc., created and maintained by unequal distribution of power. Historically (and as this book will argue, at present), these hierarchies place, for example, whites over people of color, and upper-class groups over other socioeconomic classes. Adams, Bell, & Griffin (1997) shed light on four ways oppression manifests itself among the dominant- and non-dominant groups in the hierarchy:

● The dominant group has the power to projects its culture and norms so thoroughly that they become the prevailing definition of “regular” and “correct.”

● The hierarchy confers benefits and advantages to the dominant group, yet denies them to subordinate groups. Such inequality is “business as usual.”

● The dominant group misrepresents the subordinate group through, for example, stereotypes, distorting history, or stifling the voices can threaten the arrangement or demand its restructuring.

● Members of the subordinate group may internalize the narratives of inferiority imposed by the dominant group (i.e., internalized oppression) (Delgado, 1989; Ladson-Billings, 1998).

In short, oppression is “power + prejudice” in which dominant groups—consciously or unconsciously—enjoy advantages while subordinate groups are systematically disadvantaged.

Note the use of the word group. Oppressions distinguishes between (1) individuals acts of discrimination and (2) unfair systems. While bigoted acts are of course wrong, oppression looks to the structural level. This brings us to another term: privilege.

What is privilege?

Privilege refers to the unearned benefits the dominant group receive simply by being in the group. As Swalwell (2013) notes, privileged groups are “positioned by power relations within systems of supremacy . . . that are made stronger when rendered invisible, consciously or not, to those who benefit from them most” (pp. 5-6). Because individuals in the dominant group see their way as normal, they can easily stay blind to the structures that hold their position in place. Even privileged individual who actively work against oppression reap the benefits. A white educator can devote a career to anti-racism, but is still unlikely to be pulled over, followed in a store loan, or assumed to be less capable due to skin color. Thus, privilege does not require intentionally seeking gain.

Privilege does not brush away the value of hard work. Many people rightfully pride themselves on their individual efforts; however, as the book will explore, members of non-privileged groups are more likely to face barriers to educational- and economic opportunities. Moreover, members of privileged groups enjoy the benefit of the doubt that their position is due to initiative alone. A white male who gets an executive position is less likely to be suspected of being a “token” hire than is a woman of color. For a more thorough analysis of privilege, readers may consult Adams, & Bell (2016); McIntosh (1988), and Swalwell (2013).

If you’re in a dominant group, maybe you’re thinking, “What privilege? I know a [person from non-dominant group] who has it better than me.” This brings us to intersectionality, the idea that we have multiple, overlapping identities that can grant advantages in one category and disadvantages in another (Crenshaw; 1991). For example, a former student, a white female who grew up in poverty, initially resisted the idea of “white privilege.” But when students of color from the same socioeconomic situation shared the discrimination they faced when seeking a job and a loan, the women realized that her race got her in the door more easily. The point is not to “keep score” in a contest of oppression, but rather to recognize that our complex identities reflect interconnected hierarchies.

To counter oppression, social justice aims to dismantle unjust systems and structures. Social justice aims for an outcome—“full and equitable participation” by members of all social group (Bell, 2016, p.1)—through an inclusive process that’s “mutually shaped” to meet everyone’s needs. From this perspective, society is not a fixed hierarchy, but rather a circle that can grow larger and provide opportunities to all (Clegg, 1992).

Interested in learning more? Check out my book and its free Facilitator Guide (available without purchase).

And stay tuned: In upcoming posts, I’ll be taking readers inside my social justice course at the University of Michigan. You’ll find overviews, key questions, suggestions for readings, and even assignments.

The future is a story our children will write.

The future is an unfinished story. Today’s children will write tomorrow’s chapters. Learning must prepare them to think like storytellers: to imagine possibilities and shape the plot to create the story they want.

Read MoreOne Message, Two Faiths

Facing the first holiday season without either parent—a tough end to a wrenching year for all—I felt a need to communicate gratitude. This post offers two perspectives, one each honoring my Jewish mother and my Catholic father.

Read MoreIn honor of my father

In this personal post, I reflect upon the life of my father and his influence on my life; he passed away in September.

Read More"I feel that I've just accepted a mission." New Teachers Speak on Equity in a Pandemic

Over the summer, I taught a course on education reform to forty-four graduate teaching interns just beginning an intensive one-year Master’s program at the University of Michigan. When it was confirmed that I’d be teaching it (back in February), little did I know it was going to be online. And, little did the interns know their fall student teaching might be online as well.

Given the class is based on educational equity and social justice, I integrated the equity implications of the coronavirus into the syllabus and had interns select a specific topic of interest. Some chose K-12 students’ mental health or physical wellbeing, while others compared the hidden inequities in online, hybrid, and in-person instruction.

The immediacy and complexities of these issues upped the ante for considering access, opportunity, democracy, and the common good. And while it would have been easier to simply focus on the nuts-and-bolts of teaching during a pandemic, these students rose to the higher challenge.

The interns’ commitment offers inspiration to all educators as we head into a school year rife with uncertainty. Ever the proud teacher, I am inspired to share some of the take-aways here. Each of the bulleted paragraphs is an excerpt from a different student’s work (presented anonomously with students’ permission).

We must not lose sight of the democratic purpose of education.

“I have always believed that it is our civic duty to improve our community, however, I hadn’t thought about the fact that our society seems to expect adults to solve community problems when they are rarely given an education on how to do so. It is very important to me as an educator that I am able to integrate solving global and community problems into my curriculum.”

“If you want students to learn democracy, let them practice democracy. Give them meaningful choices, teach them to collaborate, and spur them to civic action.Schools should be organized to provide a just and democratic education to all Americans so that they can participate in society.”

“Not only are we aware of the importance of equity and democracy in a classroom, but we know how to identify it based off of various categories, including, but not limited to accountability, involvement, policy, role of students, teachers, parents, government, etc. By building an actual set of criteria to evaluate schooling, “democracy” no longer belongs to the government or the bureaucrats; it is in the hands of teachers.”

“ ‘Democracy’ isn’t a word to accept and repeat, as some politicians would prefer, but a word to use to evaluate and challenge existing systems. Gaining understanding that there is a difference between “Democratic” and “democratic” was a moment in class where my fundamental understanding of the world shifted a little.

“We must realize that not only can standards and classroom democracy be integrated but that they must be integrated to create the culture and the environment that every child needs to succeed.”

We must center students’ well-being.

“It is clear that many students already have a deep grasp on the various inequities that are deeply embedded in the American school system and it is unfortunate that 16 year-olds are more capable at acknowledging these issues than [many decision-makers].”

“As educators, we need to make space for students to process their emotions and, if needed, to grieve. That is, we need to put student wellbeing before curricular goals in the coming school year. This is particularly true for Black and Brown students whose communities have been disproportionately impacted by the dual pandemics of coronavirus and police violence.”

“In times of uncertainty and unknowing, we can create a space where our students’ voice and insights can illuminate the path we are carving out for them -- and us.”

Inaction is injustice.

“As an aspiring educator, standing by is simply not enough. Advocating for our students’ behalf, especially those who are predisposed to be underrepresented or underserved, is part of our duty to increase educational and democratic equity. In this sense, democracy starts in the classroom, where we can help coming generations by giving them all a voice and purpose as citizens of their communities.”

“[My role is] not to to get my seniors to vote for a candidate or even indoctrinate my students with my way of thinking. I mean that I need to stand up for democratic equitable principles in my class, that I need to facilitate political discussions in my class, and I need to take on inherently political subjects because those subjects affect all of our lives and avoiding them does a disservice to my students.”

“Upper-class students are taught to lead, middle-class students to deliberate, and working-class students to obey. Deficit thinking justifies the perpetuation of these educational inequalities by separating students into “cans” and “cannots.” Whereas middle- and upper-class students are encouraged to take initiative and think critically, working-class students are given seatwork and detentions. To break this mold, educators need to radically rethink what each and every one our students can achieve when given the opportunity.”

We must continuously evaluate the impacts of educational policies

“If educational policy is not addressing things like access to food and clean water then it is inherently incomplete. If we are asking how to raise students’ test scores, while those same students are taking tests on empty stomachs then perhaps we need to take a look at our priorities. Policies which are not concerned about the student as a whole often rely on deficit thinking.”

“Unregulated and unmitigated competition erodes equity. When we focus on winning at all costs, the most vulnerable people are not protected. This is particularly damaging in schools, because the “losers” are not bankrupt companies, but children who miss out on an education and a future.”

“I believe that I have the tools to interpret, call out, and advocate for educational policies. By gaining skills to interpret and critically evaluate programs, we are huge assets to our schools, as we can determine what is truly democratic and equitable versus what may “sound” democratic but actually perpetuate further inequities.”

“[When talking] about No Child Left Behind and Common Core and charter schools, we should not just demonize other perspectives, but truly think critically about what’s at stake, who’s benefiting, what the underlying principles or assumptions are, and how a policy or practice may seem positive, but actually be problematic. We must truly analyze a policy’s effects and potential discrepancies.”

We must rely on each other.

“I [realize] I’m not teacher all alone in my head, trying to figure out how I was going to work around a myriad of obstacles (e.g. school board, standardized testing, administration, funding) getting in the way of me providing my students with the best educational opportunities -- I was part of an alliance, working to tear apart bad systems at their foundations, to replace inequities with actionable community efforts.”

“Communication, empathy, and flexibility are going to become our new best friends.”

You can see why I had to share these wise words. Teaching is a profession that’s under fire even on a good day, yet my student have bravely embarked on this journey under extraordinary circumstances.

To ensure all students receive the education they deserve, we must all accept the mission to not compromise our commitment to justice, even--and especially--during this pandemic. I hope you’ve found some inspiration here!

Live webinar Aug 23rd. Aligning Writing to K-12 Standards: What Teachers Need and What Authors Should Know

White Woman, Power, and Fear: The Deadly Consequences for Black Men

To the “Karens” who use their whiteness as a weapon: Stop, think, and understand the consequences for Black Men.

Read MoreTeachers to nation: We are not on vacation

With the Corona virus shuttering schools across the nation (and world), I’ve been hearing a lot of snide remarks that educators are embracing this as an early vacation. For the record, let me assure you that we are not. We are working harder than ever to ensure our students continue learning.

We are using technology in new ways to provide the interactivity so vital to learning.

We are finding creative ways to support students without internet access.

We are arranging one-on-one video meetings with students who rely on the classroom community for social- and emotional connection.

We are close captioning recordings as added support, esp. for students who are hearing impaired or whose first language is not English.

We are responding to students' emails days, nights, and weekends.

We are championing equity and access for all, knowing the upheaval students and families now face.

We are condemning anti-Asian bigotry and squelshing the ignorance that fuels it.

We are missing the casual chats, the classwide jokes, the loving teasing.

We are mourning the lost graduations, the darkened silents stages, the diplomas not claimed, the caps not thrown, the silenced cheers, the arms without students to hug.

And we willingly accept the emotional cost of deeply caring about the students we serve.

In other words, we are here for you.

Sharpen your pencils! March writing events events for children’s writers/illustrators

As I look out the window on this cold February day, snow covers my lawn and the windchill factor is dropping into the teens. But with spring (theoretically) around the corner (it is Michigan, after all), professional learning opportunties are already sprouting for the children’s literature community. Here are two I’ll be checking out in southeast Michigan:

Building Your Nonfiction Toolbox

The Michigan Society for Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators is sponsoring Building Your Nonfiction Toolbox, a one-day “one-day, jam-packed nonfiction writing conference.,” according to the event’s website. The conference will feature Carol Hinz, the Editorial Director of Lerner Books; artist and writer Heather Montgomery. and author-illustrator Lindsay Moore. Topics will include developing ideas, authenticity, primary vs. secondary sources, and special sessions for illustrators.

Day: March 7, 2020, 8:00 am to 5:00 pm

Location:VistaTech Center at Schoolcraft College, 18600 Haggerty Rd. Livonia, Mi.

Kidlitcon

This two-day conference is generously sponsored by the Ann Arbor District Library (meaning it’s free!). Session topics include Indigenous representations in children’s literature, empowering youth through literature, and using different genres to broaden children’s understanding of the world.

Days: March 27-28, 2020

Location: Ann Arbor, Michigan for our 2020 conference.